One Young Hero of the Circus FireThe story of Donald E. E. Anderson

by M. Skidgell, May 4, 2015.

On July 30, 1930, Donald Ewald Ellquist Anderson was born, the first and only child of Lillian (Ellquist) and Ewald O. Anderson. Lillian and Ewald were married in 1929 and lived with Lillian’s parents, Carl and Elin Ellquist, at their home on Winthrop Street in New Britain. After graduating from Goodwin Tech School and taking some classes at Hillyer College and Central Connecticut State College, Ewald initially found work as a draftsman in the local aircraft industry.

| |||||||

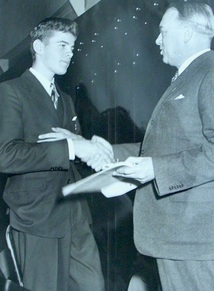

1944 newspaper photo of Donald Anderson

1944 newspaper photo of Donald Anderson

Donald E. E. Anderson and his parents were dealt some unfortunate circumstances when he was five years old. After falling on an icy sidewalk, Donald would endure nearly 5 years of hospitalization for his injuries and complications, reported to have included extended stays at New Britain General Hospital and Seaside Sanitarium in Niantic, which was also used for children with tuberculosis at the time. A plaster cast that was used on Donald caused pressure on a bone, which stunted the growth of his leg. Numerous surgeries were required; Donald wore a special shoe that was made for him, and he required the assistance of a cane to walk. He and his parents would move from the Ellquist household in 1942 and into their own home on Erdoni Road in Columbia, about 40 miles east of New Britain and closer to Windham Vo-tech School, where Donald’s father taught math and drafting for 30 years until his retirement in 1969.

On July 6, 1944, just a few weeks shy of his 14th birthday, Donald was visiting with his Ellquist grandparents at their home in New Britain when family acquaintance John “Axel” Carlson took the boy to see the circus in Hartford. Axel’s relationship to the Ellquist and Anderson family is unclear – he’s been referred to as Donald’s uncle, Donald’s cousin, Carl Ellquist’s cousin, Carl’s nephew, the family handyman, and a boarder. Axel immigrated to the United States from Sweden around the turn of the century, and took up residence in the home of fellow Swedish immigrant Carl Ellquist soon after his arrival. Never married, Axel had lived with the Ellquist family for over 40 years, and he would be buried in the Ellquist family plot after his death in 1947.

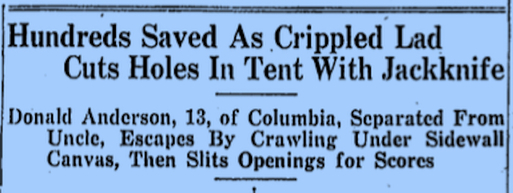

Donald’s story about his experience at the circus in Hartford was first made widely known on Sunday morning, July 9, 1944; three days after the tragic fire destroyed the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey big top in Hartford, Connecticut. Residents of the state had been listening to the radio and reading in the newspapers about all of the pain, suffering, and death over the last few days, and Donald’s story was a heroic tale of survival. Perhaps the Hartford Courant news reporter even embellished Donald’s story a bit, knowing how the readers would appreciate a “good news” story such as Donald’s. The story was on page one of the Sunday morning newspaper.

On July 6, 1944, just a few weeks shy of his 14th birthday, Donald was visiting with his Ellquist grandparents at their home in New Britain when family acquaintance John “Axel” Carlson took the boy to see the circus in Hartford. Axel’s relationship to the Ellquist and Anderson family is unclear – he’s been referred to as Donald’s uncle, Donald’s cousin, Carl Ellquist’s cousin, Carl’s nephew, the family handyman, and a boarder. Axel immigrated to the United States from Sweden around the turn of the century, and took up residence in the home of fellow Swedish immigrant Carl Ellquist soon after his arrival. Never married, Axel had lived with the Ellquist family for over 40 years, and he would be buried in the Ellquist family plot after his death in 1947.

Donald’s story about his experience at the circus in Hartford was first made widely known on Sunday morning, July 9, 1944; three days after the tragic fire destroyed the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey big top in Hartford, Connecticut. Residents of the state had been listening to the radio and reading in the newspapers about all of the pain, suffering, and death over the last few days, and Donald’s story was a heroic tale of survival. Perhaps the Hartford Courant news reporter even embellished Donald’s story a bit, knowing how the readers would appreciate a “good news” story such as Donald’s. The story was on page one of the Sunday morning newspaper.

Connecticut Governor Raymond E. Baldwin, 1944

Connecticut Governor Raymond E. Baldwin, 1944

The Hartford Courant story reported that Donald crawled under the canvas sidewall of the big top to get out, then ran along the sidewall outside and slit openings with his jackknife for more than 300 people to escape, including his “uncle” Axel. The Anderson’s were soon flooded with people asking about Donald and complementing him for his heroism. Donald was indifferent to it all, and hadn’t even told his family about what he had done until another newspaper called them looking for a photo of their son. When the story appeared in the New Britain Herald, the local paper for Donald’s grandparents, there were even more neighbors, friends and acquaintances with congratulations for Donald. Someone at the newspaper office forwarded the article to Connecticut governor Raymond E. Baldwin with a note suggesting that he contact the young hero. Within days of seeing the article that was sent to him, Governor Baldwin penned a letter to Donald Anderson, commending him for his “presence of mind and energetic efforts in making it possible for many to get out”.

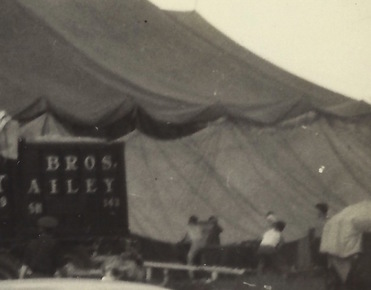

Men lifting the canvas sidewall at the southeast corner of the big top, similar to what Donald described in his letter to the governor.

Men lifting the canvas sidewall at the southeast corner of the big top, similar to what Donald described in his letter to the governor.

Donald and his mother read the letter from Governor Raymond E. Baldwin, and Lillian Anderson had her son write a reply. Donald took this opportunity to tell the governor exactly what happened, in his own words. “I wish you to know that I did not go around the circus tent and make several openings as described in the newspapers and over the radio.” While Donald didn’t do exactly what the media was heralding him for, his actions were nonetheless heroic. As he told his story in a letter to the governor just 3 months after the fire, he explained that when he first noticed a trickle of fire, he jumped down from the top of the bleachers and had to crawl under the canvas sidewall that was tied to the ground with ropes and stakes. When he got outside, he cut the ropes that held the canvas down and lifted the canvas wall, making it possible for people to crawl under and escape. He went back inside to find his “cousin” Axel, but instead found an injured girl who he helped get out safely, then went back into the roaring inferno again, for Axel. This time they found each other and got 25 feet outside of the big top when it collapsed.

Lillian (Ellquist) Anderson

Lillian (Ellquist) Anderson

Lillian Anderson sent a letter to the governor as well, explaining that Donald has received letters and accolades from many who have heard and read about his heroism at the circus fire. She even included a copy of a letter from a doctor who praised Donald for what he had done. With her son’s best interests in mind and believing that his handicap would hold him back in life, she apologetically asks the governor to contact her about discussing the possibility of an award for what her son has done, perhaps even a college scholarship.

Connecticut Governor Raymond E. Baldwin presents an award to Donald E. E. Anderson for his heroics at the Hartford circus fire.

Connecticut Governor Raymond E. Baldwin presents an award to Donald E. E. Anderson for his heroics at the Hartford circus fire.

Governor Baldwin forwarded Mrs. Anderson’s letter to University of Connecticut President Albert Jorgensen as soon as he read it, and with the governor’s recommendation that Donald be given consideration for a scholarship “in light of the boy’s heroism and in addition to the fact that he’s crippled,” Jorgensen agreed to contact Mrs. Anderson to discuss the boy’s future. Meanwhile, Governor Baldwin also made arrangements for Donald to be presented with the Connecticut Medal for Distinguished Civilian War Service at a State Capitol ceremony in November.

Donald had more surgery done on his leg during his teenage years, and his mother would work out the details with the president of the University of Connecticut. In 1948, after graduating from Windham High School, Donald went to college in pursuit of a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University’s College of Arts and Sciences which he would earn in June, 1955. During his time as a college student, he met Miss Lois Buckman and in February, 1953, they were quietly married in Maryland. On August 9, 1953, their first son is born, Donald E.E. Anderson, Junior.

The early years for the new Anderson family would be typical and ordinary for the time; two more sons would follow, grandparents doted on the little ones, mother tended to the children and participated in their school events, father finished his education and began a career in the insurance field, working with the Hartford Fire Insurance Group then as an agent for John Hancock Insurance. By 1969, however, Donald and his wife Lois were separated; an uncontested divorce was granted to Lois in 1970 on the grounds of cruelty. And things would get worse for the Anderson’s in July, 1975.

Donald had more surgery done on his leg during his teenage years, and his mother would work out the details with the president of the University of Connecticut. In 1948, after graduating from Windham High School, Donald went to college in pursuit of a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University’s College of Arts and Sciences which he would earn in June, 1955. During his time as a college student, he met Miss Lois Buckman and in February, 1953, they were quietly married in Maryland. On August 9, 1953, their first son is born, Donald E.E. Anderson, Junior.

The early years for the new Anderson family would be typical and ordinary for the time; two more sons would follow, grandparents doted on the little ones, mother tended to the children and participated in their school events, father finished his education and began a career in the insurance field, working with the Hartford Fire Insurance Group then as an agent for John Hancock Insurance. By 1969, however, Donald and his wife Lois were separated; an uncontested divorce was granted to Lois in 1970 on the grounds of cruelty. And things would get worse for the Anderson’s in July, 1975.

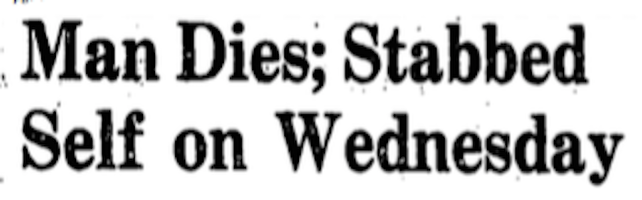

Headline from The Hartford Courant, July 11, 1975

Headline from The Hartford Courant, July 11, 1975

Donald and Lois’s oldest son, twenty-one year old Donald E. E. Anderson Jr., was living in Manchester and worked as a mechanic in West Hartford. On July 10, 1975, Hartford police were called to an apartment at 194 Washington Street. Upon their arrival, Donald Jr. was reported to have grabbed a kitchen knife and he began stabbing himself in the chest while the police watched. Despite efforts to save his life, he would succumb to these wounds at Hartford Hospital the following day. Donald’s connection to the Lafayette Arms apartment building or its residents isn’t clear, but the address can be found in many news reports during the mid-1970s for police and criminal activity, including murder, shootings, break-ins, fires (including a death by fire), nude dancers, and heroin users.

Photo of Donald Anderson from 1997 Willimantic Chronicle story.

Photo of Donald Anderson from 1997 Willimantic Chronicle story.

Donald E. E. Anderson Sr. would marry again in 1983, and divorce again 10 years later. He would retire from the insurance business in 1995 and spend his time fishing and collecting coins. Donald appeared in two documentary programs about the Hartford circus fire in 2000 and 2005, and would give more details about his escape, perhaps even editing his story to fit what was repeatedly published in the newspapers and credited to him over the years. His story and his life would sadly end on February 22, 2012, when he died at his home in Manchester at age 81. Donald E. E. Anderson was buried in the Ellquist family plot, beside his first son, Donald, Jr., and Axel Carlson.

Compilation of video interviews with Donald from the 2000 and 2005 documentaries: