Memories of the Hartford Circus Fire

by Diane (Lawrence) Jonardi

Photo of Diane Lawrence from 1944, with her arm bandaged from her injury at the circus fire. Courtesy of her daughter, Dale Burns.

Photo of Diane Lawrence from 1944, with her arm bandaged from her injury at the circus fire. Courtesy of her daughter, Dale Burns.

Memories of the Hartford Circus Fire

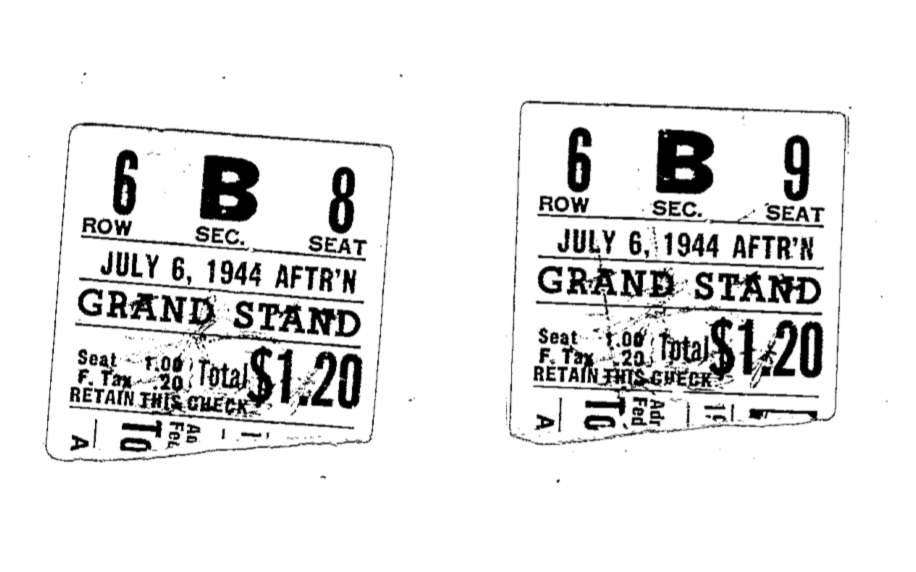

I had been looking forward to that oppressively hot day in early July. My father was taking the afternoon off from his job at the Travelers Insurance Company to take me to THE BIG circus: Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. The only other circus I’d seen was the Shrine Circus, which was held in the State Armory, not a three-ring circus with a huge Big Top and sideshows. I took the bus all alone (already an adventurous beginning) from Windsor to downtown Hartford, wearing a little yellow dress (with short, puffy sleeves) that I hated – too “little girlish” for a 12-year-old. I met my father but can’t remember now whether we walked or took a bus over to the circus. I would guess that we took a bus up to the armory and walked from there, because it seems to me we walked past the building where my aunt worked for the Connecticut Labor Department.

Never having seen any sideshows, I had been hoping that when we reached the circus we’d spend a little time seeing some of them, but we weren’t early enough to do much more than walk around, stopping to see poor old Gargantua and his mate, Toto – in separate cages, of course, because he was so “vicious” they were afraid he’d tear her to pieces. The glass sides of their air-conditioned cages were covered with condensation, so it was difficult to get a good look at Gargantua as he lay on his back, sleeping. It seemed that even with air-conditioning the heat was getting to him too.

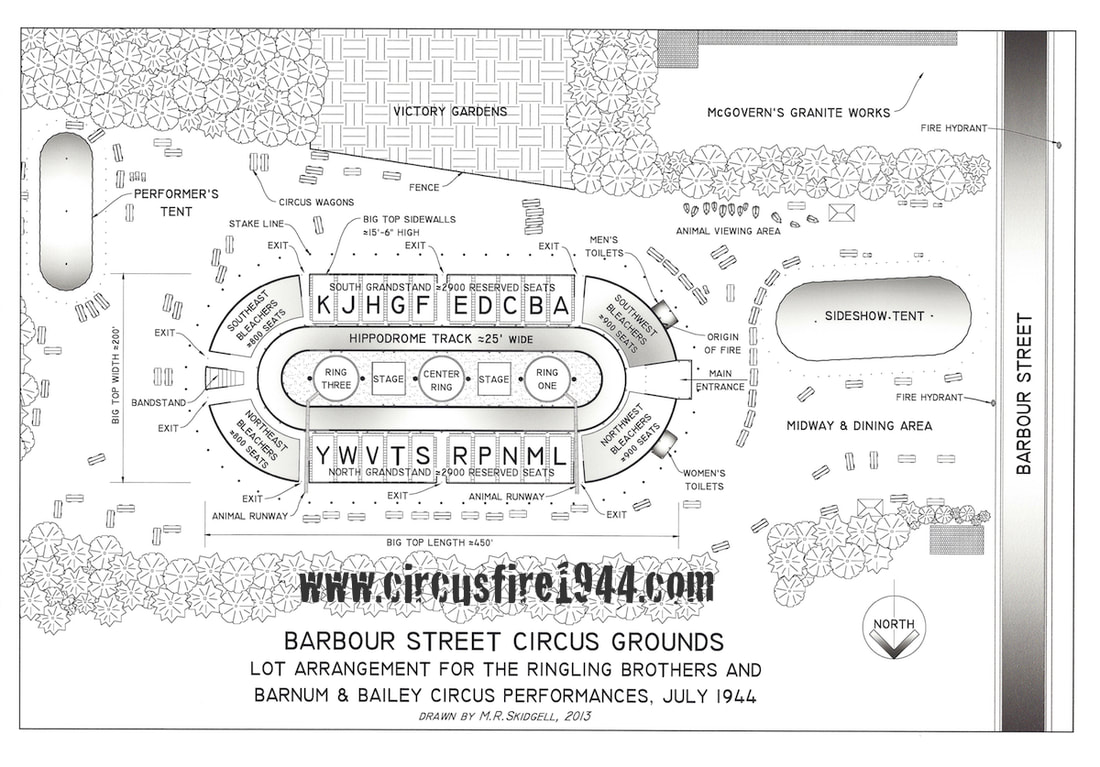

My father thought we should go to our seats to avoid the last minute rush and assured me we’d see the sideshows after the performance. We had reserved seats right by the ring nearest the main entrance. As we walked in we spotted my teacher from the previous year (6th grade), Mrs. Martha M. Menard, dressed in her Red Cross uniform, helping wounded servicemen into the bleachers adjacent to the entrance. Some of the men were in wheelchairs, sitting near the sides of the bleachers. I would guess they were probably from the military hospital up at Bradley Air Force Base in Windsor Locks. We went right to our seats, which were on the right side as we walked in, several rows up, at least ten rows. The heat in that tent was stifling, worse than standing out in the sun. Soon I was so thirsty I had to have a drink. Dad told me to stay there in my chair while he went out to get us some drinks. (Now that’s something no parent would dare do today, leave a child alone, even a 12-year-old, and I was small for my age.) Very fortunately, he returned before the circus (and the fire) started. I know if the fire had begun while I was alone, both of us would have died. I probably would have run with the crowd, he would have come back for me and never would have come out without me. Then again, who knows? I just might have waited for him to come for me. It’s a moot point now.

Finally the animals and their trainer came out into the cage in the ring in front of us and started going through their paces. I believe there were some kind of aerialists or tightrope walkers performing above the area, too. I was anxious to see the big circus parade, however, wishing they’d finish so it would start. Suddenly I heard a scream and turned to my left, looked over my shoulder and up towards the highest rows. I could see daylight through a vertical opening – a sort of column of open space where the fire had burned the side of the tent all the way up to the top. It was just then that the flames actually reached the roof of the tent. My initial thought was that it must be part of the show – things like that never happened to plain people like us. Then pandemonium broke loose. I don’t remember hearing any screams or yelling, just loud noise, a sort of roar – chairs flying, everyone stampeding past us towards the far end of the tent. My father just scooped me up and stood there holding me while the people surged around us. I don’t remember anyone even bumping into us. I put my arm around his neck, but I was concerned that I would be too heavy for him (after all, he was nearly 43 and to a skinny little 12-year-old, that seemed nearly decrepit) and begged him to put me down. He did so only after making me promise not to run. By this time the intense heat made me feel as if I were being stung all over by bees. We started down the aisle, but as we reached the railing we found two rather heavy older women in front of us. A fallen folding chair lay across the opening. The first woman was through, helping the other woman slowly trying to step over the chair. She was going to put her foot down between the rungs and take a second step to get completely over. I couldn’t wait that long. I was hurting, so as she was stepping, I gave her a little push and she stepped completely over the chair (and no, she didn’t fall or lose her balance), and we were able to squeeze past. Knowing how polite and helpful my father always was, I was so afraid he would stop and offer to help those old ladies, bit this time his manners took a back seat to self-preservation. When we reached the ground, he took a firm grip on my left upper arm to keep me from falling, not realizing that I had a second degree burn and, therefore, blisters there from when I had my arm around his neck. It had been the highest part of my body. We later discovered that he also had a second degree burn on the highest part of his body – the little bald spot on top of his head. Then, while he held my arm tightly, we “dug for it” as he put it, and raced under the fire, exiting through the main entrance, where we had originally come in. As we ran out, I glanced to the right and saw patches of fire on the ground, pieces of burning tent that had fallen? Or just burning grass? The animals and trainer were gone from the cage. I was concerned about Mrs. Menard and all those wounded servicemen – but there was no one left in the bleachers. Somehow she had managed to get them all out in time.

Once we were out of the tent, my father’s only thought was to get us out of the area. As we hurried along, I felt water trickling down my arm, and we realized that I had been burned, the water coming from the broken blisters where my father had held my arm. The elephant trainers were marching the elephants away, too; they were trumpeting and shaking their big heads from side to side as they supposedly do when disturbed. We walked back to the Connecticut Labor Department to let my aunt know we were all right. She knew nothing of the fire until then. I’m not positive, but I think before we left her, vehicles carrying bodies were starting to reach the armory. Her window overlooked the street and the armory across from it. I guess we walked back to downtown Hartford, where we caught a bus to Windsor. It’s hard to believe now that we never thought to call my mother and tell her we were OK. She was working for the OPA (Office of Price Administration) because of the war, in the Windsor Town Hall. The other ladies working there had heard the news of the fire and, knowing we were at the circus, had been trying to decide whether to tell her. They were so relieved when we walked in. Mother came to us with a big smile and said,

“What are you doing here?”

I said, “The circus burned down.”

“One of the sideshows?” she asked.

“No, the Big Top.”

Her smile faded. “Was anyone hurt?”

My dad answered, “Hundreds must have died!”

With that, she burst into tears – no stoic New Englander, my mother. We showed her my burn and noticed that I looked as if I had quite a sunburn wherever my skin was exposed (first degree burns), with quite a line of demarcation on my arms at the end of the little sleeve of the hated yellow dress, which happily I never had to wear again.

Mother took me over to the drugstore to get something to put on my burn, but when the pharmacist saw it, he said that we’d better get to a doctor. Naturally it was the Windsor doctor’s day off. We finally found one, Dr. McCready, who was at home and agreed to see us. He cut away the dead skin (painful), bandaged my arm, and gave mother instructions on changing the dressing twice a day. The scar was quite obvious for several years – a real attention-getter and conversation piece at first. It has faded a great deal – not really noticeable because my skin has mottled look now, caused by solar damage, the dermatologist says – or perhaps could the mottled effect be the result of the first degree burns? My dad had no noticeable scar on his head. I remember the evening when his blister broke and the water started to trickle down his forehead as he read the paper.

A state policeman (or was he a Hartford police detective? I’m not sure but he didn’t wear a uniform) came to our house to ask us many questions about our experience when they were investigating the cause of the fire. Strangely, my responses were correct. I didn’t mind talking about the fire, but I remember trembling slightly most of the time we talked.

As I’ve been writing, I’ve also trembled now and then, felt a little shaky, wept a little. Writing about getting down the aisle and our dash under the fire really took my breath away, as if I were doing it all again. Of course, it makes me miss my dad, who died in 1967 at only 66, and my mother, who died in 1994 at 96. Some memories are so vivid – such as the man who rushed past Dad and me, hurling chairs out of his way. Also, my aunt’s office with that big window, the smile on my mother’s face when she first saw us, and my Dad – quiet, staunch and steady, like a rock in a rampaging river as all those people rushed by. I never even thanked him for saving my life – but, after all, I guess that’s what a father is supposed to do – at least in his kid’s eyes. I used to be stoic, like him, but as I get older, I cry more easily. Writing about the fire brought it all back so strongly, just as reading about Little Miss 1565 in the Life Magazine did. When you don’t think about something for years on end, and then something like that article revives the memories, it can be pretty emotional. Anytime I read about the fire now, tears come to my eyes and it’s an effort not to weep. A kid doesn’t realize the significance or importance of things that happen to them or in the world. In my teens I saw films of our freeing the inmates of concentration camps, bodies stacked up like cordwood, gas chambers, all about the holocaust in Europe – didn’t bother me much then, but now when I see those pictures, I understand the horror and significance of it all, and the tears come. It’s the same now with the circus fire. It was an adventure then, everyone wanted to hear about it, see my scar – but now it’s frightening to realize just how lucky I was to have a father who thought before he acted and didn’t panic – lucky the fire didn’t start when I was sitting all alone, lucky it didn’t start at the other end of the tent – or I could have ended up in the armory, too, with Little Miss 1565. I have a lot to be thankful for. I have never been to a circus since, not even a sideshow, won’t even go downtown to see them march the animals from the circus train to the civic arena – after all, the one time I went to the circus, it burned down. Maybe if I were to go again, this time a lion might get loose or an elephant go berserk. Far-fetched, I know, but I have the fear.

When I read articles about the fire, I often find discrepancies and think, “No, that’s not how it was.” But I never saw any of the horrors, the burned bodies, people with their clothes burned off, skin hanging loose – and I never heard the band playing “The Stars and Stripes Forever” (but, of course, I was at the opposite end of the tent). When we started to run, it seemed so quiet – oh there was a sort of faraway background noise, and probably the sound of the flames, but, after all the people were gone, it just seems quiet in my mind.

I had been looking forward to that oppressively hot day in early July. My father was taking the afternoon off from his job at the Travelers Insurance Company to take me to THE BIG circus: Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. The only other circus I’d seen was the Shrine Circus, which was held in the State Armory, not a three-ring circus with a huge Big Top and sideshows. I took the bus all alone (already an adventurous beginning) from Windsor to downtown Hartford, wearing a little yellow dress (with short, puffy sleeves) that I hated – too “little girlish” for a 12-year-old. I met my father but can’t remember now whether we walked or took a bus over to the circus. I would guess that we took a bus up to the armory and walked from there, because it seems to me we walked past the building where my aunt worked for the Connecticut Labor Department.

Never having seen any sideshows, I had been hoping that when we reached the circus we’d spend a little time seeing some of them, but we weren’t early enough to do much more than walk around, stopping to see poor old Gargantua and his mate, Toto – in separate cages, of course, because he was so “vicious” they were afraid he’d tear her to pieces. The glass sides of their air-conditioned cages were covered with condensation, so it was difficult to get a good look at Gargantua as he lay on his back, sleeping. It seemed that even with air-conditioning the heat was getting to him too.

My father thought we should go to our seats to avoid the last minute rush and assured me we’d see the sideshows after the performance. We had reserved seats right by the ring nearest the main entrance. As we walked in we spotted my teacher from the previous year (6th grade), Mrs. Martha M. Menard, dressed in her Red Cross uniform, helping wounded servicemen into the bleachers adjacent to the entrance. Some of the men were in wheelchairs, sitting near the sides of the bleachers. I would guess they were probably from the military hospital up at Bradley Air Force Base in Windsor Locks. We went right to our seats, which were on the right side as we walked in, several rows up, at least ten rows. The heat in that tent was stifling, worse than standing out in the sun. Soon I was so thirsty I had to have a drink. Dad told me to stay there in my chair while he went out to get us some drinks. (Now that’s something no parent would dare do today, leave a child alone, even a 12-year-old, and I was small for my age.) Very fortunately, he returned before the circus (and the fire) started. I know if the fire had begun while I was alone, both of us would have died. I probably would have run with the crowd, he would have come back for me and never would have come out without me. Then again, who knows? I just might have waited for him to come for me. It’s a moot point now.

Finally the animals and their trainer came out into the cage in the ring in front of us and started going through their paces. I believe there were some kind of aerialists or tightrope walkers performing above the area, too. I was anxious to see the big circus parade, however, wishing they’d finish so it would start. Suddenly I heard a scream and turned to my left, looked over my shoulder and up towards the highest rows. I could see daylight through a vertical opening – a sort of column of open space where the fire had burned the side of the tent all the way up to the top. It was just then that the flames actually reached the roof of the tent. My initial thought was that it must be part of the show – things like that never happened to plain people like us. Then pandemonium broke loose. I don’t remember hearing any screams or yelling, just loud noise, a sort of roar – chairs flying, everyone stampeding past us towards the far end of the tent. My father just scooped me up and stood there holding me while the people surged around us. I don’t remember anyone even bumping into us. I put my arm around his neck, but I was concerned that I would be too heavy for him (after all, he was nearly 43 and to a skinny little 12-year-old, that seemed nearly decrepit) and begged him to put me down. He did so only after making me promise not to run. By this time the intense heat made me feel as if I were being stung all over by bees. We started down the aisle, but as we reached the railing we found two rather heavy older women in front of us. A fallen folding chair lay across the opening. The first woman was through, helping the other woman slowly trying to step over the chair. She was going to put her foot down between the rungs and take a second step to get completely over. I couldn’t wait that long. I was hurting, so as she was stepping, I gave her a little push and she stepped completely over the chair (and no, she didn’t fall or lose her balance), and we were able to squeeze past. Knowing how polite and helpful my father always was, I was so afraid he would stop and offer to help those old ladies, bit this time his manners took a back seat to self-preservation. When we reached the ground, he took a firm grip on my left upper arm to keep me from falling, not realizing that I had a second degree burn and, therefore, blisters there from when I had my arm around his neck. It had been the highest part of my body. We later discovered that he also had a second degree burn on the highest part of his body – the little bald spot on top of his head. Then, while he held my arm tightly, we “dug for it” as he put it, and raced under the fire, exiting through the main entrance, where we had originally come in. As we ran out, I glanced to the right and saw patches of fire on the ground, pieces of burning tent that had fallen? Or just burning grass? The animals and trainer were gone from the cage. I was concerned about Mrs. Menard and all those wounded servicemen – but there was no one left in the bleachers. Somehow she had managed to get them all out in time.

Once we were out of the tent, my father’s only thought was to get us out of the area. As we hurried along, I felt water trickling down my arm, and we realized that I had been burned, the water coming from the broken blisters where my father had held my arm. The elephant trainers were marching the elephants away, too; they were trumpeting and shaking their big heads from side to side as they supposedly do when disturbed. We walked back to the Connecticut Labor Department to let my aunt know we were all right. She knew nothing of the fire until then. I’m not positive, but I think before we left her, vehicles carrying bodies were starting to reach the armory. Her window overlooked the street and the armory across from it. I guess we walked back to downtown Hartford, where we caught a bus to Windsor. It’s hard to believe now that we never thought to call my mother and tell her we were OK. She was working for the OPA (Office of Price Administration) because of the war, in the Windsor Town Hall. The other ladies working there had heard the news of the fire and, knowing we were at the circus, had been trying to decide whether to tell her. They were so relieved when we walked in. Mother came to us with a big smile and said,

“What are you doing here?”

I said, “The circus burned down.”

“One of the sideshows?” she asked.

“No, the Big Top.”

Her smile faded. “Was anyone hurt?”

My dad answered, “Hundreds must have died!”

With that, she burst into tears – no stoic New Englander, my mother. We showed her my burn and noticed that I looked as if I had quite a sunburn wherever my skin was exposed (first degree burns), with quite a line of demarcation on my arms at the end of the little sleeve of the hated yellow dress, which happily I never had to wear again.

Mother took me over to the drugstore to get something to put on my burn, but when the pharmacist saw it, he said that we’d better get to a doctor. Naturally it was the Windsor doctor’s day off. We finally found one, Dr. McCready, who was at home and agreed to see us. He cut away the dead skin (painful), bandaged my arm, and gave mother instructions on changing the dressing twice a day. The scar was quite obvious for several years – a real attention-getter and conversation piece at first. It has faded a great deal – not really noticeable because my skin has mottled look now, caused by solar damage, the dermatologist says – or perhaps could the mottled effect be the result of the first degree burns? My dad had no noticeable scar on his head. I remember the evening when his blister broke and the water started to trickle down his forehead as he read the paper.

A state policeman (or was he a Hartford police detective? I’m not sure but he didn’t wear a uniform) came to our house to ask us many questions about our experience when they were investigating the cause of the fire. Strangely, my responses were correct. I didn’t mind talking about the fire, but I remember trembling slightly most of the time we talked.

As I’ve been writing, I’ve also trembled now and then, felt a little shaky, wept a little. Writing about getting down the aisle and our dash under the fire really took my breath away, as if I were doing it all again. Of course, it makes me miss my dad, who died in 1967 at only 66, and my mother, who died in 1994 at 96. Some memories are so vivid – such as the man who rushed past Dad and me, hurling chairs out of his way. Also, my aunt’s office with that big window, the smile on my mother’s face when she first saw us, and my Dad – quiet, staunch and steady, like a rock in a rampaging river as all those people rushed by. I never even thanked him for saving my life – but, after all, I guess that’s what a father is supposed to do – at least in his kid’s eyes. I used to be stoic, like him, but as I get older, I cry more easily. Writing about the fire brought it all back so strongly, just as reading about Little Miss 1565 in the Life Magazine did. When you don’t think about something for years on end, and then something like that article revives the memories, it can be pretty emotional. Anytime I read about the fire now, tears come to my eyes and it’s an effort not to weep. A kid doesn’t realize the significance or importance of things that happen to them or in the world. In my teens I saw films of our freeing the inmates of concentration camps, bodies stacked up like cordwood, gas chambers, all about the holocaust in Europe – didn’t bother me much then, but now when I see those pictures, I understand the horror and significance of it all, and the tears come. It’s the same now with the circus fire. It was an adventure then, everyone wanted to hear about it, see my scar – but now it’s frightening to realize just how lucky I was to have a father who thought before he acted and didn’t panic – lucky the fire didn’t start when I was sitting all alone, lucky it didn’t start at the other end of the tent – or I could have ended up in the armory, too, with Little Miss 1565. I have a lot to be thankful for. I have never been to a circus since, not even a sideshow, won’t even go downtown to see them march the animals from the circus train to the civic arena – after all, the one time I went to the circus, it burned down. Maybe if I were to go again, this time a lion might get loose or an elephant go berserk. Far-fetched, I know, but I have the fear.

When I read articles about the fire, I often find discrepancies and think, “No, that’s not how it was.” But I never saw any of the horrors, the burned bodies, people with their clothes burned off, skin hanging loose – and I never heard the band playing “The Stars and Stripes Forever” (but, of course, I was at the opposite end of the tent). When we started to run, it seemed so quiet – oh there was a sort of faraway background noise, and probably the sound of the flames, but, after all the people were gone, it just seems quiet in my mind.

In memory of Albert Lawrence and Diane (Lawrence) Jonardi.

Courtesy of daughter and granddaughter, Dale J. Burns.

Courtesy of daughter and granddaughter, Dale J. Burns.

July 22, 1944, the Lawrence family received a visit from a Connecticut State Police officer to interview them about their experience at the circus fire. Albert Lawrence's statement, from the Connecticut State Police files, can be downloaded here:

| lawrence_albert_witness_statement.pdf | |

| File Size: | 3519 kb |

| File Type: | |